Legal professionals from around the world talk about ethics.

Over three days in July, Fordham’s Stein Center for Law and Ethics welcomed prominent academics, practicing lawyers, and regulators for the seventh International Legal Ethics Conference. The event, spearheaded by Stein Center Director Bruce Green and Associate Director Sherri Levine, featured more than 80 programs on a range of topics including access to justice, international rule of law, challenges to judicial integrity, and professional regulation.

More than 400 participants from 60 countries attended.

Here, nine of them speak about their experiences.

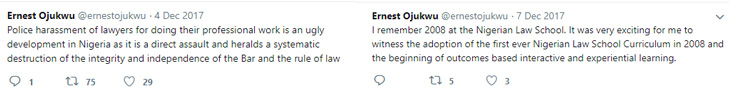

Ernest Ojukwu | Nigeria

With the many problems concerning legal ethics in his home country of Nigeria, it was not easy for Ojukwu to find sponsorship to attend ILEC.

“When discussing problems facing the nation, people identify ethics, corruption, and lack of discipline as challenges,” he said. “But when you ask for action, these problems are taken off the table. It is difficult to find institutions that have enough funding to fight the problems of ethics and lack of discipline.”

Ojukwu has been heavily involved with integrating legal ethics into Nigerian culture, especially at universities throughout the country. He is also very active in the Nigerian Bar Association and is currently focusing on access-to-justice issues, especially in litigation.

“I am very interested in building a culture of ethics in my home country, particularly at the educational level. So I am excited to see and hear from colleagues who have taught ethics and to learn how they have integrated ethics into their cultures.”

At ILEC, Ojukwu spoke about integrating the concept of legal ethics at the academic level. His panel, “Actions Speak Louder Than Words: The Ethical Law School,” discussed the challenges various institutions from around the world face with improving legal ethics training.

“The best forum to talk about legal ethics is at the educational level, particularly starting when students are at a younger age,” he said.

Ojukwu has been practicing law since 1984 and is a professor of law in Nigeria. He also serves as president of the Network of University Legal Aid Institutions (NULAI).

“The NULAI in Nigeria has helped about 19 law faculties establish law clinics, for which we were able to develop an ethics curriculum and integrate into the mainstream of law school clinical courses,” he said.

Ojukwu and his fellow ILEC panelists encouraged participants to reflect on what is right and wrong in regard to legal ethics, as well as to discuss measures that can be taken to train law students to become more ethical lawyers, in spite of the many challenges imposed by society. He noted that the conference’s diversity is integral to facilitating such changes.

“The diversity of participants at the conference is very important. Ethics is an international problem. Because cultures differ, it is fundamental to understand how each country is grappling with the challenges of ethics. With that kind of diversity we can learn a lot from each other.”

Ahmed Al-Hawamdeh | Jordan

Al-Hawamdeh, an associate professor of corporate law at Jerash University, traveled to ILEC so that he could learn from other countries’ experiences and implement better practices in Jordan.

“I expect to get a feel for what’s going on around the world and hopefully find solutions to problems that we encounter back home in Jordan,” he said. “Jerash University is trying to better prepare students for the market and not leaving it up to the chance of them having good training after they graduate. We really want to make sure that our students are acquiring the skills they need.”

Since legal ethics is not a focus of the curriculum at Jerash (a relatively new university only 25 years old, with approximately 300 students), Al-Hawamdeh had a difficult time finding sponsorship to attend ILEC. Fortunately, he was one of about 40 participants who received a travel subsidy disbursed by Fordham Law.

Speaking on the same ethics-in-legal-education panel as Ojukwu, Al-Hawamdeh believes ILEC provides an invaluable opportunity for meeting people from all parts of the world.

“The conference is a great chance to talk with people and hear their different perspectives,” he said. “Based on others’ experiences, I will hopefully learn something that I can take back home to Jordan.”

Al-Hawamdeh earned his undergraduate degree in his home country, later studied in Scotland at the University of Aberdeen, and then obtained a Ph.D. in England. Since his return to the Middle East, he has worked tirelessly to reform Jordan’s system of legal education, including involving students more in issues related to helping the underprivileged or those who don’t have access to justice.

He feels the international range of academics at ILEC is the key for improving legal ethics, because it is a venue where everyone can share their experiences and solutions.

“In order to prepare students on ethical issues, you need to have common solutions,” he said. “What you learn from looking at others’ experiences and how they manage to overcome the obstacles they face gives you strength to carry on and believe that something will come of it.”

Olga Churakova | Kyrgyz Republic

Access to legal aid is a global concern. Defense lawyers, who serve as protectors of the human right to due process and a fair trial, face challenges in every country. Without access to effective legal counseling, individuals are at risk of being detained arbitrarily or illegally—or worse, they may even be wrongfully convicted or subject to torture.

Motivated to right these wrongs, Churakova directs the Advocates’ Training Center in the Kyrgyz Republic to improve the professional knowledge of advocates so that they can provide the highest level of quality legal service to the country’s citizens. By traveling to ILEC, Churakova hoped to learn new ways in which she could increase opportunities for advocates and spread awareness of legal ethics norms in her country.

“With participants from more than 60 countries present at the conference, there is a very interesting opportunity to learn everything about legal ethics throughout the world and to improve the systems of our countries where we are living and working,” Churakova said.

“With participants from more than 60 countries present at the conference, there is a very interesting opportunity to learn everything about legal ethics throughout the world and to improve the systems of our countries where we are living and working,” Churakova said.

In 2014, the Kyrgyz Republic developed a new legal ethics code for advocates, which paved the way for the inclusion of ethics training in basic courses. Churakova noted that one of the biggest challenges surrounding legal ethics in her country is advocates having to deal with conflicts of interest while remaining ethical.

“I think that every advocate has struggled with some difficult ethical question in their professional career, but oftentimes there is no one for them to consult with on what to do in such a situation,” she said.

At ILEC, Churakova spoke on the “Building Defense Bar Capacity to Ensure Equality of Arms” panel. She said that advocates in the Kyrgyz Republic are not generally held in the same regard as judges and prosecutors.

“The advokatura [the bar]has to be put on the same level as the prosecutor’s office in order to protect human rights. We are trying to disseminate our new ethics code and improve advocates’ training,” she said.

The Advocates’ Training Center intends to continue the process of improving legal ethics training of advocates and lawyers of the country through teaching sessions.

“Networking at the conference was extremely important to discussing legal ethics issues. It was a great opportunity to meet the specialists and experts

from around the world,” Churakova said. “I’m very glad to have been invited. I would have never imagined I could have attended such a conference. It is exciting to learn the experiences of other countries.”

Suphamat “Bee” Phonphra and Nattakan “Ann” Chomputhong | Thailand

Jetlagged but excited for their first visit to the United States to attend ILEC, Phonphra and Chomputhong came as representatives of Bridges Across Borders Southeast Asia Community Legal Education Initiative (BABSEACLE), an international organization working to strengthen access to justice, legal ethics education, and community empowerment.

At the core of BABSEACLE’s mission is the belief that access to justice is an ethical responsibility. Through clinical legal education, the organization aims to foster community service–minded lawyers and pro bono advocates to help extend legal assistance in often marginalized communities.

Phonphra, an access-to-justice initiative coordinator, and Chomputhong, a legal trainer and legal ethics and professional responsibility initiative coordinator, were drawn to work with BABSEACLE because they saw firsthand the lack of adequate legal ethics education in Thai universities, a situation that is only recently beginning to change.

“When I was a student, the lectures did not inspire me about how to be a good lawyer,” said Phonphra. “I didn’t know until I had worked for four or five years, and now I understand more.”

“My university was a bit different,” noted Chomputhong. “When I was a student we had legal ethics, but just one credit, so we did not learn much.”

Now both women train lawyers, students, and educators throughout Asia, using an interactive and practical curriculum for teaching legal ethics created by BABSEACLE in collaboration with international law firms, teachers, and government partners.

The BABSEACLE curriculum provides a needed core structure of legal ethics education, which can be adapted to different legal systems depending on the country in which it is taught.

So far the curriculum has been implemented in several Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar.

In their ILEC session, Phonphra, Chomputhong, and two BABSEACLE colleagues modeled their interactive approach to teaching the curriculum, which uses group work and role-playing to have students engage with real ethical issues they would encounter in practicing law.

Though both women acknowledge that there is still much work to do to spread legal ethics education throughout Asia, they have seen progress since working with BABSEACLE.

“Through the clinical legal education program, not just lawyers but also students who work in the clinics provide free legal advice and also do community teaching,” said Chomputhong.

Going forward, both women hope to encourage more regional people to get involved in their movement and also further cultivate the interchange of ideas and resources with international lawyers and educators, as they did at ILEC.

“We would welcome more suggestions for effective methods or tools that we can use to improve legal ethics teaching in Asia,” said Chomputhong. Referring specifically to lawyers and educators from non-Southeast Asian countries, she continued, “They are welcome to come and assist in any training provided, any materials they can share.”

Phonphra seconded Chomputhong’s call for further international collaboration. “Contact us!” she said with a broad smile.

Zoha Savadkouhifar | Iran, Pakistan

When Savadkouhifar was a legal adviser and researcher in Iran, she had the opportunity to evaluate the state of legal ethics in the country by working with different judiciary departments and academic programs such as legal clinics and also studying the larger context of Iranian constitutional law.

She recognizes that Iranian constitutional law and other legislative and administrative laws already provide structures and procedures to oversee and regulate the behavior of lawyers and judges, and she understands that constitutional law in Iran incorporates Islamic law, which sets forth specific rules for the independence and impartiality of judges. However, she believes that laws alone cannot ensure justice if lawyers and judges are not educated in how ethics should be applied in the many facets of their professional practice.

“We all know that when the person is not trained, whatever the law is won’t work,” she said.

“We all know that when the person is not trained, whatever the law is won’t work,” she said.

For Savadkouhifar, currently a Ph.D. candidate at Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto University of Law in Pakistan, what is needed in Iran is a stronger commitment to legal ethics education in the country’s law schools.

She has seen the consequences of inadequate training; she once confronted a family court judge who was compelling a woman to stay in a marriage because the judge did not believe the behavior of the husband was harsh enough to grant the divorce the woman was seeking.

“I told him, ‘This woman came to your court to access justice. You are violating her more than her husband is,’” she said.

In the past few years, Savadkouhifar has seen some progress in Iran, including the introduction of legal ethics courses and legal clinics in universities; workshops for judges, police officers, and court workers; and discussions of legal ethics by bar associations.

“What I can say is that I am hopeful for the next generation,” she said.

One area in which she has passionately applied her expertise to bring about change is juvenile justice, where important advancements have been made recently. Savadkouhifar has played key roles in some Iranian national projects, including “Model Law on Management of Juvenile Correctional Departments” and “Developmental Crime Prevention through Schools for Children at Risk,” now implemented in three pilot schools.

Savadkouhifar, whose husband is from Pakistan, where they now live, is currently a member of the Pakistan bar association. At ILEC she spoke on a panel titled “Legal Ethics and Legal Education in Two Islamic Republic Countries,” and she is eager to continue learning about legal ethics in international and comparative contexts. She is now an LL.M. student at Penn State Law and will continue her Ph.D. in Pakistan next summer.

“If we really want to do such things as policymaking in my country, nowadays we cannot do anything if we don’t know what is going on in the international environment.”

Martin Bohmer | Argentina

“In Argentina, the joke is that legal ethics is optional,” said Bohmer, opening his ILEC presentation as part of a panel on the state of legal ethics in Latin America.

Though the remark was met with genial laughter by the assembled panelists and audience members, it pointed to a serious reality of legal education in Argentina.

Argentina.

“Mostly there are no courses on legal ethics,” said Bohmer. “And when we do teach it, it’s an optional subject in the law school.”

As a professor of legal theory at Universidad de Buenos Aires Law School, where his own legal ethics course is optional, Bohmer has often had to convince his students that the subject is not a trivial matter.

“So the first thing I found that I needed to do in the classroom was to create a sort of gravitas in the atmosphere—to put things in a more dramatic light,” he said.

In the classroom, Bohmer tries to awaken students to the life-altering impact their work as lawyers may have on others.

“You are going to take away children from someone, you are going to put somebody in prison, you are going to destroy relationships, you are going to start a bankruptcy of a corporation,” he tells them.

He hopes to cultivate a reflective capacity within his students that will help them take proper actions as lawyers.

Bohmer also wants his students to see the way legal ethics are connected to a much broader national context and serve as the foundation for the rule of law in Argentina as a whole. His point is that if lawyers fail to act in good faith, are dishonest or unscrupulous, then codes of procedure cannot work as they should.

“If you cannot make a code of procedure work, then you cannot make the civil code, the criminal code, the law work,” he said. “And if you cannot make the law work, you cannot make the constitution work.”

His students’ attitudes change, he said, “once they realize that we are dealing with legal ethics not just to be nice but to fulfill the role of the lawyer in a constitutional democracy.”

Currently, Bohmer is serving as national director in the Ministry of Justice of Argentina, where he is assisting in the first-ever process of accreditation of law schools. As part of this project, law schools across Argentina have recognized the need to include legal ethics courses, though a lack of qualified faculty and necessary teaching materials often hinders the achievement of this goal.

“So my job now is to finance the development of materials to teach, and then with those materials to train the trainers who will teach,” said Bohmer.

Russell Pearce | New York

Hip hop rhythms from the acclaimed Broadway musical Hamilton played in the background as participants assembled for an ILEC session discussing relational perspectives on ethics and the legal profession, the first of its kind at an international legal ethics conference.

As the music faded out, Pearce, the session’s moderator, explained the musical’s connection to the subject at hand.

“Hamilton was, after all—whatever you think of his politics—a person who valued the role of relationships in politics,” he said.

A professor at Fordham Law since 1990, Pearce has focused on relational theory as an important part of his examination of what creates a just legal system and the role that lawyers play in providing justice in society.

His work on relational theory questions the widely held “atomistic” view prevalent in law, business, and politics today, which sees individuals and organizations operating separately from each other.

“An atomistic actor in any of these areas thinks, ‘What can I get away with?’” said Pearce.

According to him, the atomistic actor “is the measure of self-interest, because you are separate and your self-interest doesn’t have to take into account your friend, your neighbor, your colleagues, or your community.”

For Pearce, the consequences of this mindset can have damaging consequences in our society, including “incivility in politics, short-term thinking in business, and hired-gun approaches in law,” he said.

In reality, “it’s a myth that anyone or any organization is atomistic,” he said.

“Every successful lawyer, every successful business person recognizes at some level that their success depends on their relationships.”

Debunking the atomistic myth is necessary to fight narrow self-interest, he said, and on a broader level, combat the problems of income inequality and gender and racial injustice.

Pearce, who is Jewish, also focuses part of his work on religion and law, cultivating among lawyers who are religious a dialogue about how faith can inform legal practice and education. He serves as the faculty director of Fordham’s Institute on Religion, Law, and Lawyer’s Work.

His broad interests include the study of the ways that new technologies, such as online legal services company Legal Zoom, are changing the profession and the market. Though these technologies can provide legal assistance to those who perhaps could not otherwise afford it, they are currently unregulated in the United States.

“As we better understand where technology is going, we’ll have a better understanding of how to regulate in the interests of protecting consumers, protecting society, and providing broad access to justice,” he said.

Xiaobing Liu | China

Having studied law in the United States and China, Liu has a solid understanding of the differences in legal ethics education in the two countries.

In his view, China is making progress but still lags behind the United States and other western countries in instilling legal ethics in students and addressing problems with conflicts of interest, breaches of client privacy, and other forms of misconduct on the part of lawyers.

“In China the economy has grown up, but rule of law is backward, so there is a difference,” he said. “In the United States and most western countries the rules are very detailed; in China they are far from detailed.”

As a professor at China University of Political Science and Law, he is doing his part to improve the situation as the director of the only university department in the country devoted to the study of legal ethics.

Liu and his faculty of 11 professors are part of a movement to professionalize the study of law in China, where a student does not need to attend law school before taking the bar exam.

In his ILEC talk, Liu outlined recent legal ethics reforms set forth by the Chinese central government, and also the challenges faced in their implementation, including inconsistent standards among government offices, underdeveloped educational programs, and a lack of qualified faculty.

“In China the situation is getting better, but we still have a lot of problems,” he said. “That’s why we call it a crisis of legal ethics because many lawyers do not comply.”

To illustrate his point, Liu gave the example of the much-publicized case involving Tianyi Li, the teenage son of a Chinese general convicted of rape in 2013. In the trial, Li’s lawyers attacked the credibility of the victim, described her as sexually promiscuous, and made her medical records public.

Liu himself is committed to doing pro bono work and serving in the community. “I devote my time to those who need legal aid,” he said. “In my university I also have a legal clinic. I lead, guide, and instruct the students to help those who are poor.”

Though Liu feels optimistic about the future potential of legal practice in China, he also knows real change won’t happen overnight.

“Of course it takes time to implant the idea of legal ethics in every lawyer’s mind,” he said.

Story by Samantha Mathewson and Nina Heidig, photographs by Chris Taggart