In the cosmology of African communities, naming rituals are very important because the name tells a story and predicts destiny. When on 23 September 1960, Helen Nmemahialuka (Nmema) Ikeanyionwu gave birth to her son, she called him “Madu-abu-chi” – no human is God.

Nearly two and a half years before, on 26 April, 1958, Nmema got wedded to Robert Nwokeocha Ojukwu Ikeanyionwu at the grand old age of 25. Born, Mmema Atulomah, she was a teacher from Umuahia in the then Eastern Region (now Abia State) working in Oturkpo in the then Northern Region (now Benue State), the daughter of a Methodist missionary, who had the privilege of early access to education; Robert was a Produce Inspector, servant expert in the aggregation and standardization of various primary products for export, including the famous peanut pyramids of Kano. Their mutual journey down the aisle began with a chance meeting the previous year on a train journey to their respective work stations in northern Nigeria.

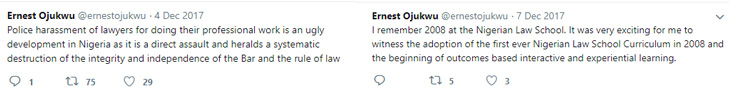

At 25, the neighbourhood whisper then was that Nmema was well past the age of marriage and her education was to blame. Her first pregnancy miscarried. When she lost the child from her second pregnancy shortly after birth, another statistic in child mortality, the frenzy of naysaying from the neighbourhood shamans took on a life of its own. Her answer to them was in the name she gave to her son. Madu-abu-chi was at once an affirmation of her faith, a prayer to her Creator and an embodiment of her hopes for him. Upon being baptized in the Methodist faith, the child was given the name Ernest. In time, Madu-abu-chi would also come to define the message and mission of the child, “earnest” became his method. Today, we know him as Professor Maduabuchi Ernest Ojukwu, Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) and the father of clinical legal education in Nigeria.

Maduabuchi unlocked fertile fortunes for Nmema, who would go on to have nine children, sadly losing two. She was a teacher among teachers. She ran schools as head-teacher and was a fearsome political organizer and long-time executive member of the Nigerian Union of Teachers (NUT), in the old Imo State in south-eastern Nigeria. In that role, around 1982, she survived an assassination attempt, miraculously escaping with the graze of a bullet to her forehead, in Umuahia, current capital of Abia State. Retiring from the public service as a supervisor of schools, Nmema plunged into livelihood advocacy for women and became a proprietor of a genre-defining El-Shaddai Foundation Daycare-Nursery-Primary School, Ahaba, in Isuikwuato, Abia State, her vision was to enhance the educational status of the rural child, with the motto, “Shine that others may see”. When she died 12 years ago, Nmema bequeathed the management of the children in the school – all 350 of them – as a trust to a team with one message: Madu-abu-chi. The Chair of the trustees was her Maduabuchi. Message and mission had become one.

Today, Maduabuchi, a third generation teacher on his maternal side, lives out his natal mission, enabling children in the entire educational value chain from nursery to graduate school in Nigeria and beyond to fulfill their dreams and realise their ambitions, safe in the knowledge that no human is god over them.

I was a witness to its beginning. In September, 1985, a young man walked into my undergraduate criminal law class in the then Imo State University in a temporary site in Aba. He carried no notes, no pads and no airs. He knew the Criminal Code like the back of his hand and the relevant texts like he slept with them. He made learning a joy to be part of. He had completed his high school at Government College Umuahia, after a stint at Methodist College Uzuakoli (the high school from which his dad graduated in 1952), before taking a degree in law from Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, graduating at the very top of his class in 1983. He was admitted to the Nigerian Bar in 1984, the same year that Mmema retired from the public service, before becoming our teacher from that memorable day in 1985, having joined the staff of the university as an assistant lecturer in 1985, at the end of his compulsory national service programme. Ten years later, at 35, he became Dean of Law at the same faculty, by then known as Abia State University, a position from which he would propel it into one of the top law faculties in the country.

All this while, he was also active in legal practice and in the organized legal profession, becoming chair of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) in Aba and later founder of the Eastern Bar Forum. His academic and legal practice careers met at the confluence of the Nigerian Law School, where he became Deputy Director-General and head of the Enugu Campus for 12 years from 2001. It was from there that he founded what would become the Network of University Legal Aid Institutions (NULAI), in 2004, in a collaboration with Isa Hayatou Ciroma and Yemi Akinseye George, becoming its president. All of them are incidentally now law professors and SANs, confirming the point that a professional trajectory does not have to be predictable.

In the beginning, only four law faculties were willing to act as Guinea Pigs for law clinics in Nigeria: Abia State University, Uturu; Adekunle Ajasin University in Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State; University of Maiduguri; and Federal University, Uyo, Akwa Ibom state. Again, I was a witness at that modest beginning, and, with colleagues from the Open Society Justice Initiative, played a part in facilitating the onset of that journey but the vision belonged to Madu-abu-chi. In 2017, the National Universities Commission, NUC, made law clinics compulsory in all Nigerian law faculties. Today, 43 different university-based law clinics are registered with NULAI and making inestimable contributions to both legal education and justice services delivery across the country.

In a lifetime of investment in Nigeria’s legal profession, Madu-abu-chi engineered mandatory, continuing legal education in the legal profession and, in 2007, ensured the enactment of the current set of Rules of Professional Conduct (RPC) in the Legal Profession in Nigeria. When he was elevated to Silk in 2014, it was an overdue acknowledgement of a life of consequential service to education, the legal profession and public life. Back home in Isuikwuato, he is a traditional chief, known by the appellation of Gbaonwa Gbaonwa Agbonelu of Ahaba Imenyi, and the Ugomba of Imenyi Kingdom in Isuikwuato.

While it is indeed true that madu-abu-chi, it is also the case that no one authors their destiny all by themselves. Every trajectory in life gets the benefit of ancestors and helpers along the way. Maduabuchi has been helped along by Ijeoma, a judge of the Federal High Court of Nigeria who presides over his heart and home and who is also a former student. At 60, he has a lot more to give and, if the past is a foretaste of what is to come, the best may yet still be ahead.

Chidi Anselm Odinkalu, a lawyer, is co-convener of Nigeria Mourns. He writes in his personal capacity